A Life in the Struggle for Civil Rights

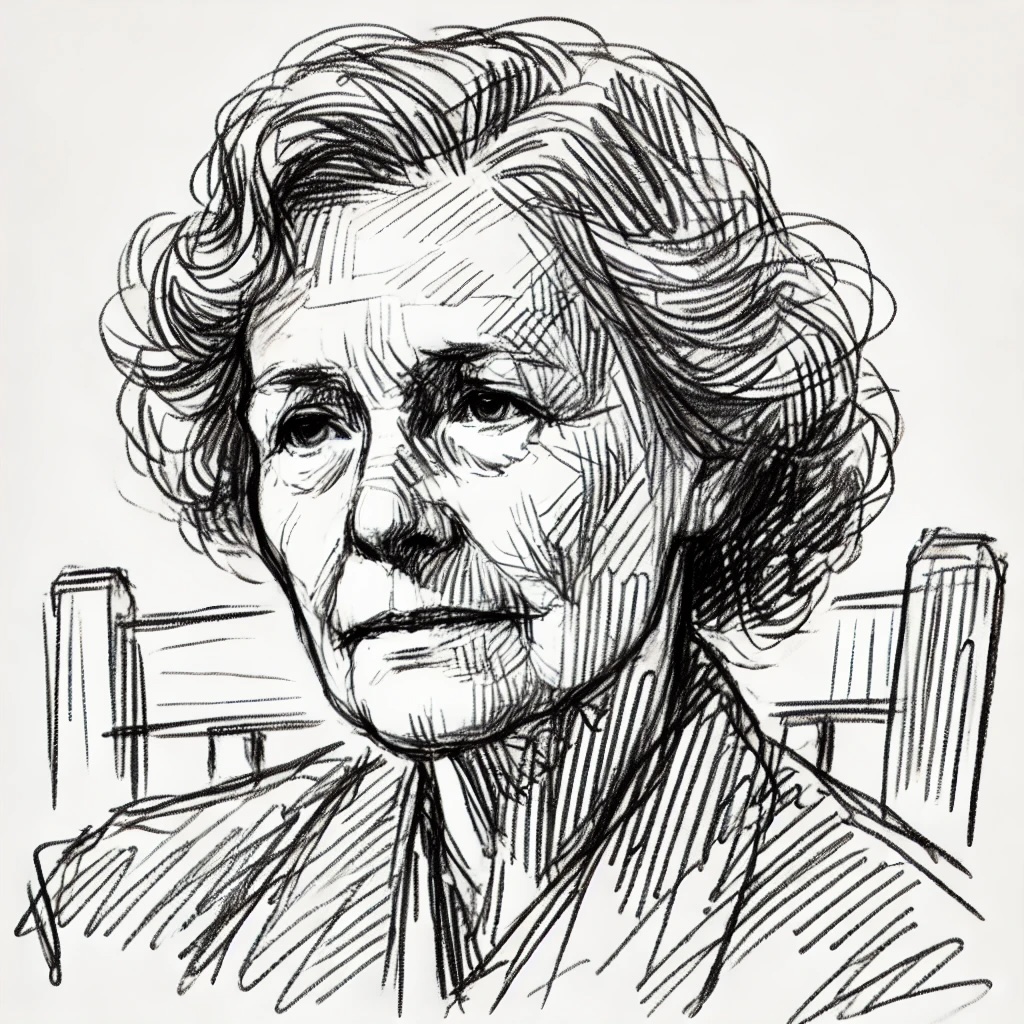

Anne McCarty Braden was born on July 28, 1924, in Louisville, Kentucky, into a middle-class white family. Raised in Anniston, Alabama, her early years were steeped in the segregated culture of the South. However, Anne’s experiences and observations would soon lead her to question and ultimately reject the racist norms of her upbringing.

As a young journalist in Birmingham, Alabama, in the 1940s, Anne encountered firsthand the stark realities of racial injustice. She later recalled a pivotal moment when she saw a Black woman drinking from a “colored” water fountain:

“I remember consciously thinking, ‘She’s drinking this water and I’m drinking that water, and it doesn’t make any sense,’” Braden said in a 1989 interview. “And I think that was the beginning of my realization that there was something terribly wrong here.”

This awakening set Anne on a path that would define the rest of her life – a relentless pursuit of racial equality and social justice.

The Wade Case: A Turning Point

In 1954, Anne and her husband Carl Braden made headlines when they purchased a house in an all-white Louisville suburb on behalf of Andrew Wade IV, a Black World War II veteran, and his family. This act of defiance against housing segregation unleashed a storm of controversy and violence.

The struggle for civil rights is not a black issue; it is a human issue. If we don’t fight for each other, we will all be lost.

Anne Braden

The Wades moved into their new home on May 15, 1954, but their residency was short-lived. White neighbors, enraged by the presence of a Black family in their midst, mounted a campaign of intimidation and terror. Crosses were burned on the lawn, shots were fired into the house, and on June 27, the home was dynamited.

Instead of investigating the perpetrators of these hate crimes, local authorities turned their attention to the Bradens. Carl was indicted on charges of sedition, accused of plotting to blow up the house to incite unrest. Anne later wrote about this harrowing period in her book “The Wall Between”:

“We had expected trouble, but we had not expected this… We had not realized the depths of the sickness in our society.”

The Wade case thrust Anne into the national spotlight and solidified her commitment to the civil rights movement. Despite the personal cost – Carl served eight months in prison before his conviction was overturned – the Bradens remained steadfast in their beliefs.

A Life of Activism and Education

Following the Wade case, Anne dedicated herself fully to the cause of civil rights. She and Carl became field organizers for the Southern Conference Educational Fund (SCEF), traveling throughout the South to support integration efforts and challenge racist policies.

We were called communists, traitors, and we received death threats. But we felt it was our duty to stand up for what was right.

Anne Braden

Anne’s work went beyond organizing; she was also a prolific writer and editor. From 1957 to 1973, she edited “The Southern Patriot,” SCEF’s monthly newspaper, which became an important voice for the civil rights movement. Her writing style was direct and unflinching, as evidenced in this excerpt from a 1958 article:

“The South’s real problem is not desegregation – it is democracy. The whole country’s problem is not racial discrimination – it is democracy.”

In addition to her journalistic work, Anne authored several books, including “The Wall Between” (1958), which was nominated for the National Book Award. Her writings often explored the role of white Southerners in the struggle for racial justice, challenging her peers to confront their own prejudices and join the fight for equality.

Personal Life and Interests

While Anne’s public life was dominated by her activism, she also had a rich personal life and diverse interests. She was an avid reader with a particular fondness for Southern literature. In her later years, she often spoke about the importance of storytelling in the struggle for social justice.

Anne was also deeply interested in music, particularly folk and protest songs. She saw music as a powerful tool for social change and often incorporated songs into her organizing work. In a 1995 interview, she reflected on the role of music in the movement:

“Those songs gave us strength. They reminded us why we were fighting and brought us together in a way that nothing else could.”

Despite the challenges and dangers of her work, Anne maintained a sense of humor and joy in life. Friends and fellow activists often remarked on her warmth and ability to find hope in even the darkest situations.

Legacy in Louisville

Anne’s connection to Louisville, Kentucky, remained strong throughout her life. After the Wade case, she and Carl made the city their permanent home, and it became the base for much of their activism.

In Louisville, Anne was involved in numerous local struggles, from school desegregation to fair housing initiatives. She was a fixture at demonstrations and community meetings, always ready to lend her voice and experience to the cause.

One of Anne’s most significant contributions to Louisville was her role in founding the Kentucky Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression in 1975. This organization became a hub for progressive activism in the city, addressing issues from police brutality to environmental justice.

Anne’s impact on Louisville was perhaps best summed up by long-time friend and fellow activist Bob Cunningham, who said in a 2005 interview:

“Anne wasn’t just part of Louisville’s civil rights history – she helped shape it. She challenged this city to live up to its ideals, and she never stopped pushing for justice.”

Later Years and Continued Activism

Even in her later years, Anne remained active in social justice causes. She was a vocal opponent of the Vietnam War, spoke out against the Gulf War in the 1990s, and in her final years, protested the Iraq War.

We are all part of the struggle for justice, and it is our collective responsibility to stand up against oppression.

Anne Braden

Anne also became a mentor to younger generations of activists, sharing her experiences and wisdom. She taught classes on civil rights history at the University of Louisville and Northern Kentucky University, inspiring students with her firsthand accounts of the movement.

In a 2002 interview, reflecting on her life’s work, Anne said:

“People always ask me if I’m passing the torch. I always say, ‘Oh there’s no passing the torch. I’m using my torch to light other people’s torches.’ Because that’s what we did in the movement. It’s not a relay race. We’re all running together.”

Final Days and Enduring Impact

Anne Braden passed away on March 6, 2006, at the age of 81. Her death was mourned by activists and community members across the country, but particularly in her adopted hometown of Louisville.

At her memorial service, held at the Presbyterian Community Center in Louisville, speakers from various generations and backgrounds testified to Anne’s impact on their lives and on the ongoing struggle for justice.

Civil rights leader Reverend C.T. Vivian, in his eulogy, captured the essence of Anne’s legacy:

“Anne Braden was not just an ally in the civil rights movement. She was a sister in the struggle. She understood that racism hurts us all, and she committed her life to healing that hurt. Her courage, her clarity, and her unwavering commitment will continue to inspire us for generations to come.”

Today, Anne Braden’s legacy lives on through the countless individuals she inspired and the organizations she helped build. The Anne Braden Institute for Social Justice Research at the University of Louisville, established in 2007, continues her work by promoting scholarship and activism around issues of racial and social justice.

Anne Braden’s life serves as a powerful reminder of the role that committed individuals can play in the long arc of social change. Her journey from a child of the segregated South to a lifelong warrior for justice demonstrates the possibility of transformation and the power of unwavering dedication to principle.