The Outlaw Journalist

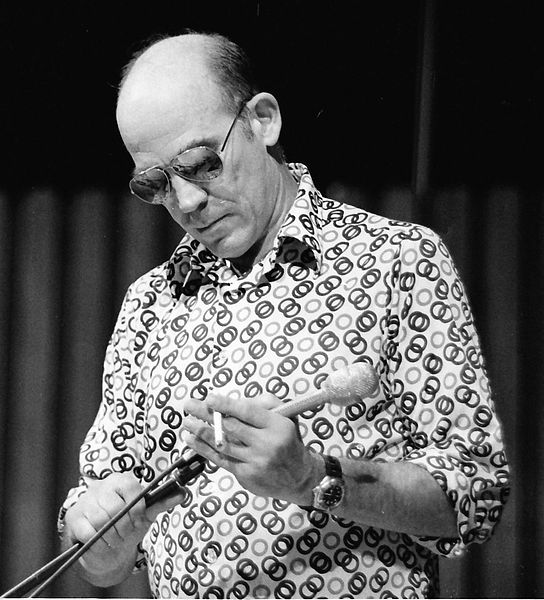

Hunter S. Thompson was a whirlwind of chaos, a wild-eyed renegade who blurred the lines between journalist and participant, prose and pandemonium. His life was a maelstrom of hard truths, savage humor, and rabid pursuit of freedom in a world he saw as increasingly absurd. Thompson didn’t just report on America’s underbelly—he lived there, waded knee-deep through its darkest waters, and reported back with a fury only he could muster. Known as the mad prophet of Gonzo journalism, Thompson left behind a trail of shattered conventions and mind-bending literary feats, proving himself not only as a writer but as a cultural phenomenon.

Born into the Louisville Abyss

Hunter Stockton Thompson, born July 18, 1937, emerged screaming into a world that he would later describe as both beautiful and grotesque. He grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, a city of bourbon and horse racing, where he felt southern gentility was often a veil for hypocrisy.

Thompson had an early distaste for authority and pretense—traits that would grow into a full-fledged rebellion during his adolescence. His father’s early death in 1952 cast a long shadow over his life, leaving his mother to raise him and his two brothers alone. The absence of a father figure, coupled with his mother’s descent into alcoholism, likely fueled the chaotic tendencies that would later define him.

In high school, Thompson’s anti-establishment streak was already evident. He was a member of the prestigious Athenaeum Literary Association, an elite society that included some of Louisville’s most privileged young men, but even within this group, he was an outsider. In 1956, his antics landed him in jail for robbery, and while this brush with the law cemented his reputation as a local outlaw, it also marked the beginning of his long struggle with conventionality. He was expelled from school and narrowly avoided a more severe punishment by enlisting in the Air Force. Yet, Louisville never truly left him. His Southern roots, with all their contradictions, were etched into his soul, influencing his worldview, his writing, and the strange, crooked path his life would take.

Thompson’s relationship with his hometown was as jagged and complex as the man himself. He often ridiculed Louisville for its stifling atmosphere and conservative mores, yet he never fully abandoned it. “I resented Louisville because I was stuck there,” he once admitted, “but at the same time, I knew it would always be a part of me.” That tension would permeate much of his work, a war between love and disdain, tradition and rebellion, civility and savagery.

Thompson didn’t just report on America’s underbelly—he lived there, waded knee-deep through its darkest waters, and reported back with a fury only he could muster.

The Birth of Gonzo: A Blazing, Drug-Fueled Revolution

By the late 1960s, Thompson had drifted across the country, picking up odd journalism jobs and writing dispatches that always carried a certain manic energy. But it wasn’t until 1970 that he struck literary gold. His breakthrough came in the form of an assignment for Scanlan’s Monthly, where he was asked to cover the Kentucky Derby—a prestigious event swathed in Southern decadence. But what Thompson delivered wasn’t the crisp, clean race report the magazine had anticipated. Instead, “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved” was a booze-soaked, hallucinatory account of the event, a fever dream that spiraled far from the horse track. It was a riotous blend of fact and fiction, with Thompson at the center of the storm.

Gonzo journalism was as much a personal manifesto as it was a style. For Thompson, the only honest way to report the world’s madness was to dive headfirst into it.

This piece gave birth to Gonzo journalism—a term coined by Thompson’s friend and editor Bill Cardoso, who, upon reading the Derby story, exclaimed, “This is pure Gonzo!” Thompson later defined Gonzo as a style “with no claims to objectivity,” where the writer was not a passive observer but an active participant. The writer became part of the story, twisting reality with a combination of drugs, booze, and raw emotion, while still delivering biting, often vicious truths about American culture.

Gonzo journalism rejected the clinical distance that traditional reporting upheld. In Thompson’s view, that approach was dishonest. “Objective journalism is one of the main reasons American politics has been allowed to be so corrupt for so long,” he once said, with his characteristic venom. “You can’t be objective about Nixon.” Gonzo journalism was as much a personal manifesto as it was a style. For Thompson, the only honest way to report the world’s madness was to dive headfirst into it, to experience it with wild abandon, and then write it down in a blur of rage and euphoria.

Fear and Loathing: The Masterpiece and the Myth

It was with Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971) that Hunter S. Thompson reached the apex of his Gonzo style. The book was ostensibly an account of a road trip he took with his friend, lawyer Oscar Zeta Acosta (who appears as the iconic “Dr. Gonzo”), to cover a motorcycle race in the Nevada desert. But what unfolded was something far beyond simple reportage—it was a deranged odyssey through the heart of the American dream, replete with psychedelic drugs, violence, and absurdity.

In Fear and Loathing, Thompson wasn’t just chronicling a trip to Las Vegas; he was diagnosing the sickness of a nation. The book’s manic tone mirrored the instability of post-1960s America, a country reeling from the disillusionment of the Vietnam War, the failure of the counterculture, and the rise of a new conservatism. In one of its most famous lines, Thompson writes: “We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold.” This sentence encapsulates the wild abandon of the book, as well as the greater cultural breakdown it reflects.

Thompson later described Fear and Loathing as “a failed experiment in Gonzo journalism.” But its failure was, in a sense, its triumph. The book didn’t just blur the line between fiction and journalism; it bulldozed it. It was a hallucinatory commentary on the collapse of the American Dream—chaotic, erratic, and painfully honest.

Political Battles: Thompson Takes on the System

In addition to being a literary outlaw, Hunter S. Thompson was also fiercely political. He viewed America’s political system with deep suspicion and disdain, often referring to it as a “rotten machine.” His most famous foray into politics came during his campaign for sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado, in 1970. Running on the “Freak Power” ticket, Thompson sought to challenge the status quo in Aspen, where he had moved to escape the increasingly oppressive atmosphere of mainstream America.

His campaign platform was, unsurprisingly, radical. He called for the decriminalization of drugs, the tearing up of streets to create bike paths, and a ban on building that would “ruin the natural beauty” of the area. Perhaps most famously, he shaved his head completely bald so he could refer to his opponent, the conservative sheriff Carroll Whitmire, as “my long-haired opponent.”

Though Thompson narrowly lost the election, the campaign solidified his status as a political force. It also laid bare his deep contempt for the structures of power in America. He would later channel that rage into one of his finest works, Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72, which chronicled the presidential election between Richard Nixon and George McGovern. The book is a scathing indictment of the corruption and manipulation that Thompson saw in American politics. “Nixon represents the dark side of the American Dream,” Thompson wrote, summing up his view of the man he once called a “crook” and “monster.” His fierce hatred of Nixon became one of his defining characteristics, and the two would remain locked in a kind of cosmic struggle, with Nixon embodying everything Thompson despised about the country’s power structures.

The Crumbling Edges of Fame and Self-Destruction

By the late 1970s and into the 1980s, Thompson’s fame had become a burden. He was revered as a countercultural icon, but the weight of that public image began to crush him. The demand for “Hunter S. Thompson”—the drug-fueled outlaw persona—outpaced his ability to produce the kind of writing that had made him famous. He spent much of this period indulging in his own myth, living in his compound in Woody Creek, Colorado, a place known as Owl Farm, where he held court with guns, drugs, and an endless stream of visitors.

Life should not be a journey to the grave with the intention of arriving safely… but rather to skid in broadside in a cloud of smoke, thoroughly used up, totally worn out, and loudly proclaiming ‘Wow! What a Ride!’

One of his close friends, the writer Tom Wolfe, described Thompson as “a prisoner of his reputation, the Duke of Destruction in a high castle made of hallucinogenic fumes.” Thompson himself seemed aware of the trap. “I hate to advocate drugs, alcohol, violence, or insanity to anyone,” he famously said, “but they’ve always worked for me.” He was a man chasing the wild high of Gonzo—sometimes catching it, but more often slipping deeper into chaos.

The 1980s and 1990s were a period of diminishing returns for Thompson. His later works, such as The Curse of Lono and Better Than Sex, never recaptured the energy of his earlier writings. But despite the unevenness of his later output, Thompson remained a cultural touchstone, a symbol of rebellion and resistance against the establishment.

The Final Act: A Cannon’s Echo

In the early 2000s, Hunter S. Thompson’s health began to deteriorate. The physical toll of years of substance abuse, combined with a growing sense of isolation, left him in poor spirits. His writing had slowed, and he found it increasingly difficult to navigate the modern world, which he saw as sinking into a new kind of madness—one that was bureaucratic, joyless, and devoid of the revolutionary spirit he had championed in the 1960s.

On February 20, 2005, Thompson died by suicide at his home in Woody Creek, Colorado. He was 67. In a final act of defiance, Thompson’s family and friends—including Johnny Depp, who portrayed Thompson in the film adaptation of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas—honored his request to have his ashes shot from a cannon atop a 153-foot tower in the shape of a double-thumbed fist clutching a peyote button. The blast echoed through the Rocky Mountains, a fitting farewell for a man who had lived life at full volume.

Reflecting on his life, Thompson once said, “Life should not be a journey to the grave with the intention of arriving safely in a pretty and well-preserved body, but rather to skid in broadside in a cloud of smoke, thoroughly used up, totally worn out, and loudly proclaiming ‘Wow! What a Ride!’” That was the essence of Hunter S. Thompson—a man who lived without fear, who railed against convention, and who wrote with a fiery, uncontrollable force that reshaped the boundaries of journalism.

Conclusion

Hunter S. Thompson was not just a journalist; he was a cultural revolutionary, a man who fought against the constraints of society, politics, and conventional journalism with every fiber of his being. From his early days in Louisville to his final years in Woody Creek, Thompson’s life was a chaotic, thrilling ride—one that he chronicled with an unflinching, drug-fueled clarity. In an America often caught between its ideals and its hypocrisies, Thompson’s words burned like a signal flare, illuminating the absurdities and cruelties of the system. He was, in the end, a writer who didn’t just report on life—he embodied it in all its beautiful, terrifying madness.