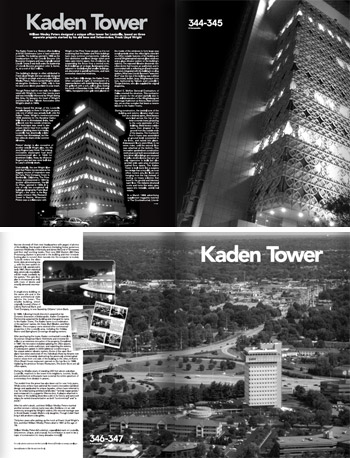

William Wesley Peters designed a unique office tower for Louisville, based on three separate projects started by his old boss and father-in-law, Frank Lloyd Wright

The Wright Tower is a 15-story office building at 6100 Dutchmans Lane in east suburban Louisville, Kentucky. The building opened in 1966 as the headquarters for the Lincoln Income Life Insurance Company and was originally named Lincoln Tower. It was built under the leadership of Lincoln Income president John T. Acree, Jr., at a cost of $2.7 million.

The building’s design is often attributed to Frank Lloyd Wright, but was actually designed by Wright’s protégé and son-in-law William Wesley Peters. Peters married Wright’s adopted daughter Svetlana in 1935, only to lose her and a son eleven years later in a car crash.

Though Peters had his own style, he collaborated with Wright for more than 20 years and was inevitably influenced by Wright during this time. He became the head of Wright’s architectural firm Taliesin Associates after Wright’s death in 1959.

Design

Peters based the design of the Louisville complex largely on three of Wright’s projects, only one of which was actually built. Like the Wright Tower, Wright’s never-constructed 1946 sketches for the Sarabhai Calico Mills Store in Ahmedabad, India, had grillwork over the outside windows. This technique was used to decrease interior heat from sunlight without blocking views from inside. Louisville has drastically colder winters than Ahmedabad, but the two cities do share similar summer climates.

Peters’ design is also evocative of another unbuilt Wright plan, the 40-story Rogers Lacy Hotel. This striking, innovative skyscraper had been commissioned also in 1946 for downtown Dallas, Texas, by oil tycoon Rogers Lacy but was never built due to Lacy’s untimely death.

Undoubtedly, the one Wright blueprint that Peters incorporated as his biggest source of inspiration for the Kaden Tower was the HC Price Company Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma.

The Price Tower, commissioned in 1952 by another oil businessman, Harold C. Price, opened in 1956. It is one of only two completed tall buildings designed by Frank Lloyd Wright – the other is the legendary Johnson Wax Research Tower in Racine, Wisconsin.

Peters was a collaborator with Wright on the Price Tower project, so it is not surprising that the Wright and Price buildings have many common components, including their distinctive cantilever design which provides open interior space, free of columns, by suspending the floors from a central core. Both buildings sit on large, landscaped sites, adjacent to similarly-styled smaller buildings, are decorated in pastel earth tones, and have somewhat obscured windows.

Like the Calico Mills design, the Wright Tower, when occupied at night, is reminiscent of a Japanese lantern with inside lighting illuminating the grillwork with a soft, yellow glow. During the month of December in the 1970s and early 1980s, transparent color gels were placed on the inside of the windows to form large seasonal symbols when the office lights were left on.

Other notable features of the building are several Wright-inspired stained glass windows and a glass elevator system on the building’s exterior. The exposed elevator descends into a low dome that houses an auditorium and is surrounded with a reflecting pool and fountain that were integrated with the building’s cooling system.

What was originally Lincoln Income’s “executive floor” near the top of the building was outfitted customized, built-in, boxy, Wright-esque furniture, fashioned by Taliesin and Louisville’s Thorpe Interiors, who also supplied the original draperies.

Construction

Robert E. McKee General Contractors of Dallas erected the structure. This contractor was chosen for the project partially due to their skillful execution of the Wright-designed Gammage Auditorium at Arizona State University, yet another complex that bears a resemblance to the Wright Tower.

During construction, the central core of the building and exterior elevator shaft rose first as a skeletal spine. Steel beams were laid across the top of the inner concrete tower, projecting to the outer perimeter of the building. Steel tension cables were then draped to the ground from the outside ends of the beams. The fourteenth floor’s frame was assembled at ground level, connected to the lines, and raised into place. Subsequent floors were lifted, in reverse order, until the second floor was attached at the bottom.

This innovative upside-down construction method proved both economical and fast. Most tall buildings are encased in bulky steel columns that are not only expensive to build but also prohibit large, open-landscape interiors. The Wright Tower is built more like a suspension bridge than a monolith, as most office towers are. Its floors are hanging from the top instead of resting on heavy columns that travel to the ground and intersect each floor. This reduces structural costs and turns the extra open space into rentable, useful real estate.

In a March 1966 advertising supplement magazine inserted in The Courier-Journal, Lincoln Income showed off their new headquarters with pages of photos of the building. Their board of directors (including former governors Lawrence Weatherby of Kentucky and James McCord of Tennessee) is shown as well as Lincoln’s staff working inside the new tower. The company’s new IBM System 360 Data Processing System is pictured in the building and their forward-looking plan to convert their records into the computer is touted. “Lincoln enters the electronic data processing era … with the new system to become fully operational in early 1967. Much statistical data, previously unavailable, will be made available by the system.” The open floor plan is showcased as well, with rows of desks and smartly-dressed secretaries.

A single-story building on the same site and in the same architectural style adjoins the tower. This smaller building, which originally housed offices of Liberty National Bank and Trust Company, is now leased by Citizens’ Union Bank.

Renovation

In 1986, following Lincoln Income’s acquisition by Conceco Insurance of Indianapolis, Kaden Companies Partnership acquired the building and changed its name to the Kaden Tower. The Kaden name is a combination of the partners’ names; Jim Karp, Bert Blieden, and Mark Blieden. The company owns several other commercial properties in the Louisville area, including the Holiday Manor and Springhurst Crossings shopping centers.

The building was known as Kaden Tower from 1986 to 2023, when it was renamed to Wright Tower in order to acknowledge the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright who – again – did not design the building .

After purchasing the tower, Kaden contracted Louisville’s Grossman Chapman Klarer Architects and invested $2 million in an extensive renovation of the property. Completed in 1987, the renovation included updating the office spaces, upgrading the onsite auditorium, and repainting the exterior. A subsequent update in 2003 added air conditioning to the unique exterior elevator system.

Some of the open floor plans have been sectioned off into individual offices by tenants over the years, unfortunately obstructing the previous interior views from one side of the building to the other.

The green landscape around the site has also been filled in over the years. Parking lots, widened roads and other office buildings now crowd the area where the Lincoln Tower once stood alone.

A Ruth’s Chris Steak House restaurant opened on the top floor in 1998, replacing the previous Terrace Restaurant. The lower floors are all office space.

Critical Reaction

During more than a half century of standing 200 feet above suburban Louisville, reactions to the Wright Tower from neighbors, tourists, locals, and architecture enthusiasts have covered the entire spectrum of commentary from disdain to praise.

The verdict from the press has also been out for over a half century. While some writers have admired the tower’s innovative cantilever design and applauded its unique façades, others have referred to it as “an embarrassing architectural blunder,” “entirely inappropriate,” and compared it to a gigantic Kleenex box. A plaque attached to the base of the building describes a bit of its history and acknowledges its varied characterization as both “controversial” and “a jewel.”

PETERS’ legacy

After his wife’s death, architect William Wesley Peters married another woman – whose name was also Svetlana – in an odd ceremony arranged by Wright’s widow. His second marriage was to Soviet leader Joseph Stalin’s only daughter. Though it didn’t last long it did produce a daughter.

Thirty-two years after picking up the torch at Frank Lloyd Wright’s firm, architect William Wesley Peters died in 1991 at the age of 79.

William Wesley Peters left a distinct, unparalleled mark on Louisville. Uncommon, unique, and unusual, his contribution is sure to be a topic of conversation for many decades more.

See also:

Google Maps street view and satellite image.

Photos and text by Scott Ritcher, excerpted from K Composite Magazine. Special thanks to Elite Air. Permission granted for use on the Wright Tower page on Wikipedia.