.mw-parser-output .plainlist ol,.mw-parser-output .plainlist ul{line-height:inherit;list-style:none;margin:0;padding:0}.mw-parser-output .plainlist ol li,.mw-parser-output .plainlist ul li{margin-bottom:0}.mw-parser-output .infobox-subbox{padding:0;border:none;margin:-3px;width:auto;min-width:100%;font-size:100%;clear:none;float:none;background-color:transparent}.mw-parser-output .infobox-3cols-child{margin:auto}.mw-parser-output .infobox .navbar{font-size:100%}@media screen{html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .infobox-full-data:not(.notheme)>div:not(.notheme)[style]{background:#1f1f23!important;color:#f8f9fa}}@media screen and (prefers-color-scheme:dark){html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .infobox-full-data:not(.notheme) div:not(.notheme){background:#1f1f23!important;color:#f8f9fa}}@media(min-width:640px){body.skin–responsive .mw-parser-output .infobox-table{display:table!important}body.skin–responsive .mw-parser-output .infobox-table>caption{display:table-caption!important}body.skin–responsive .mw-parser-output .infobox-table>tbody{display:table-row-group}body.skin–responsive .mw-parser-output .infobox-table th,body.skin–responsive .mw-parser-output .infobox-table td{padding-left:inherit;padding-right:inherit}}

Wilson Pickett | |

|---|---|

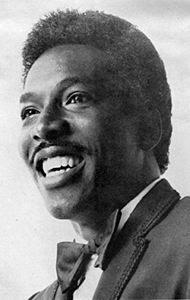

Pickett c. 1968 | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as | Wicked Pickett |

| Born | (1941-03-18)March 18, 1941 Prattville, Alabama, U.S. |

| Origin | Detroit, Michigan, U.S. |

| Died | January 19, 2006(2006-01-19) (aged 64) Reston, Virginia, U.S. |

| Genres | .mw-parser-output .hlist dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul{margin:0;padding:0}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt,.mw-parser-output .hlist li{margin:0;display:inline}.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul ul{display:inline}.mw-parser-output .hlist .mw-empty-li{display:none}.mw-parser-output .hlist dt::after{content:”: “}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li::after{content:” · “;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li:last-child::after{content:none}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li li:first-child::before{content:” (“;font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd li:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt li:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li li:last-child::after{content:”)”;font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol{counter-reset:listitem}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol>li{counter-increment:listitem}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol>li::before{content:” “counter(listitem)”\a0 “}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd ol>li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt ol>li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li ol>li:first-child::before{content:” (“counter(listitem)”\a0 “} |

| Occupations |

|

| Instrument | Vocals |

| Years active | 1955–2004 |

| Labels | |

Wilson Pickett (March 18, 1941 – January 19, 2006) was an American singer and songwriter.

A major figure in the development of soul music, Pickett recorded more than 50 songs that made the US R&B charts, many of which crossed over to the Billboard Hot 100. Among his best-known hits are “In the Midnight Hour” (which he co-wrote), “Land of 1000 Dances“, “634-5789 (Soulsville, U.S.A.)“, “Mustang Sally“, “Funky Broadway“, “Engine No. 9”, and “Don’t Knock My Love“.[3]

Pickett was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1991, in recognition of his impact on songwriting and recording.[4]

Biography

Early life and family

Pickett was born March 18, 1941, in Prattville, Alabama,[3] and sang in Baptist church choirs. He was the fourth of 11 children and called his mother “the baddest woman in my book,” telling historian Gerri Hirshey: “I get scared of her now. She used to hit me with anything, skillets, stove wood … [one time I ran away and] cried for a week. Stayed in the woods, me and my little dog.”[5] Pickett eventually left to live with his father in Detroit in 1955.[6]

Early musical career (1955–1964)

Pickett’s forceful, passionate style of singing was developed in the church and on the streets of Detroit,[4] under the influence of recording stars such as Little Richard, whom he referred to as “the architect of rock and roll.”

In 1955, Pickett joined the Violinaires, a gospel group. The Violinaires played with another gospel group on concert tour in America. After singing for four years in the popular gospel-harmony group, Pickett, lured by the success of gospel singers who had moved to the lucrative secular music market, joined the Falcons in 1959.[4]

By 1959, Pickett recorded the song “Let Me Be Your Boy” with the Primettes as background singers. The song is the B-side of his 1963 single “My Heart Belongs to You”.

The Falcons were an early vocal group bringing gospel into a popular context, thus paving the way for soul music. The group featured notable members who became major solo artists; when Pickett joined the group, Eddie Floyd and Sir Mack Rice were members. Pickett’s biggest success with the Falcons was “I Found a Love”, co-written by Pickett and featuring his lead vocals. While only a minor hit for the Falcons, it paved the way for Pickett to embark on a solo career. Pickett later had a solo hit with a re-recorded two-part version of the song, included on his 1967 album The Sound of Wilson Pickett.

Soon after recording “I Found a Love”, Pickett cut his first solo recordings, including “I’m Gonna Cry”, in collaboration with Don Covay. Pickett also recorded a demo for a song he co-wrote, “If You Need Me“, a slow-burning soul ballad featuring a spoken sermon. Pickett sent the demo to Jerry Wexler, a producer at Atlantic Records. Wexler gave it to the label’s recording artist Solomon Burke, Atlantic’s biggest star at the time. Burke admired Pickett’s performance of the song, but his own recording of “If You Need Me” became one of his biggest hits (No. 2 R&B, No. 37 pop) and is considered a soul standard. Pickett was crushed when he discovered that Atlantic had given away his song. When Pickett—with a demo tape under his arm—returned to Wexler’s studio, Wexler asked whether he was angry about this loss. He denied it, saying “It’s over”.[7] Pickett’s version was released on Double L Records as his debut solo single and was a moderate hit, peaking at No. 30 R&B and No. 64 pop.

Pickett’s first significant success as a solo artist came with “It’s Too Late”, an original composition (not to be confused with the Chuck Willis standard of the same name). Entering the charts on July 27, 1963, it peaked at No. 7 on the R&B chart (No. 49 pop); the same title was used for Pickett’s debut album, released in the same year. Compiling several of Pickett’s single releases for Double L, It’s Too Late showcased a raw soulful sound that foreshadowed the singer’s performances throughout the coming decade. The single’s success persuaded Wexler and Atlantic to buy Pickett’s recording contract from Double L in 1964.

Rise to stardom: “In the Midnight Hour” (1965)

Pickett’s Atlantic career began with the self-produced single, “I’m Gonna Cry”. Looking to boost Pickett’s chart chances, Atlantic paired him with record producer Bert Berns and established songwriters Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil. With this team, along with arranger, conductor Teacho Wiltshire[8] Pickett recorded “Come Home Baby”, a duet with singer Tami Lynn, but this single failed to chart.[3]

Pickett’s breakthrough came at Stax Records‘ studio in Memphis, Tennessee, where he recorded his third Atlantic single, “In the Midnight Hour” (1965).[9] This song was Pickett’s first big hit, peaking at No. 1 R&B, No. 21 pop (US), and No. 12 (UK).[3] It sold more than one million copies, and was awarded a gold disc.[10] It garnered Pickett his first Grammy nomination for Best Rhythm & Blues Recording at the 8th Annual Grammy Awards.[11]

The genesis of “In the Midnight Hour” was a recording session on May 12, 1965, at which Wexler worked out a powerful rhythm track with studio musicians Steve Cropper and Al Jackson of the Stax Records house band, including bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn. (Stax keyboard player Booker T. Jones, who usually played with Dunn, Cropper and Jackson as Booker T. & the M.G.’s, did not play on the studio sessions with Pickett.) Wexler said to Cropper and Jackson, “Why don’t you pick up on this thing here?” He performed a dance step. Cropper explained in an interview that Wexler told them that “this was the way the kids were dancing; they were putting the accent on two. Basically, we’d been one-beat-accenters with an afterbeat; it was like ‘boom dah,’ but here was a thing that went ‘um-chaw,’ just the reverse as far as the accent goes.”[12]

Stax/Fame years (1965–1967)

Pickett recorded three sessions at Stax in May and October 1965. He was joined by keyboardist Isaac Hayes for the October sessions. In addition to “In the Midnight Hour”, Pickett’s 1965 recordings included the singles “Don’t Fight It” (No. 4 R&B, No. 53 pop), “634-5789 (Soulsville, U.S.A.)“[13](No. 1 R&B, No. 13 pop), and “Ninety-Nine and a Half (Won’t Do)” (No. 13 R&B, No. 53 pop). All but “634-5789” were original compositions which Pickett co-wrote with Eddie Floyd or Steve Cropper or both; “634-5789” was credited to Cropper and Floyd alone.

For his next sessions, Pickett did not return to Stax, as the label’s owner, Jim Stewart, had decided in December 1965 to ban outside productions. Wexler took Pickett to Fame Studios, a studio also with a close association with Atlantic Records, located in a converted tobacco warehouse in nearby Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Pickett recorded some of his biggest hits there, including the highest-charting version of “Land of 1000 Dances“, which was his third R&B No. 1 and his biggest pop hit, peaking at No. 6. It was a million-selling disc.[10]

Other big hits from this era in Pickett’s career included his remakes of Mack Rice‘s “Mustang Sally” (No. 6 R&B, No. 23 pop), and Dyke & the Blazers‘ “Funky Broadway“, (R&B No. 1, No. 8 pop).[3] Both tracks were million sellers.[10] The band heard on most of Pickett’s Fame recordings included keyboardist Spooner Oldham, guitarist Jimmy Johnson, drummer Roger Hawkins, and bassist Tommy Cogbill.[14]

Later Atlantic years (1967–1972)

‘A Man and a Half’ is the quintessential Pickett title from this period—he’s always striving to become more than he has any reason to expect to be.

Near the end of 1967, Pickett began recording at American Studios in Memphis with producers Tom Dowd and Tommy Cogbill, and began recording songs by Bobby Womack. The songs “I’m in Love”, “Jealous Love”, “I’ve Come a Long Way”, “I’m a Midnight Mover” (co-written by Pickett and Womack), and “I Found a True Love” were Womack-penned hits for Pickett in 1967 and 1968. Pickett recorded works by other songwriters in this period; Rodger Collins‘ “She’s Lookin’ Good” and a new arrangement of the traditional blues standard “Stagger Lee” were Top 40 hits Pickett recorded at American. Womack was the guitarist on all recordings.

Pickett returned to Fame Studios in late 1968 and early 1969, where he worked with a band that featured guitarist Duane Allman, Hawkins, and bassist Jerry Jemmott. A No. 16 pop hit remake of The Beatles‘ “Hey Jude” came out of the Fame sessions, as well as the minor hits “Mini-Skirt Minnie” and “Hey Joe” (a remake of the Jimi Hendrix hit).

Late 1969 found Pickett at Criteria Studios in Miami. His remakes of the Supremes‘ “You Keep Me Hangin’ On” (No. 16 R&B, No. 92 pop) and The Archies‘ “Sugar, Sugar” (No. 4 R&B, No. 25 pop), and the Pickett original “She Said Yes” (No. 20 R&B, No. 68 pop) came from these sessions.

Pickett then teamed up with established Philadelphia-based hitmakers Gamble and Huff for the 1970 album Wilson Pickett in Philadelphia, which featured his next two hit singles, “Engine No. 9” and “Don’t Let the Green Grass Fool You”, the latter selling one million copies.[10]

Following these two hits, Pickett returned to Muscle Shoals and the band featuring David Hood, Hawkins and Tippy Armstrong. This lineup recorded Pickett’s fifth and last R&B No. 1 hit, “Don’t Knock My Love, Pt. 1”.[3] It was another Pickett recording that rang up sales in excess of a million copies.[10] Two further hits followed in 1971: “Call My Name, I’ll Be There” (No. 10 R&B, No. 52 pop) and “Fire and Water” (No. 2 R&B, No. 24 pop), a cover of a song by the rock group Free.

In March 1971, Pickett headlined the Soul To Soul concert in Accra to commemorate Ghana‘s 14th Independence Day.[16] He is featured on the soundtrack album, Soul To Soul, which peaked at No. 10 on the Billboard Soul LPs chart.[17]

Pickett recorded several tracks in 1972 for a planned new album on Atlantic, but after the single “Funk Factory” reached No. 11 R&B and No. 58 pop in June 1972, he left Atlantic for RCA Records. His final Atlantic single, a recording of Randy Newman‘s “Mama Told Me Not to Come”, was culled from Pickett’s 1971 album Don’t Knock My Love. However, six years later, the Big Tree division of Atlantic released his album, Funky Situation, in 1978.

In 2010, Rhino Handmade released a comprehensive compilation of these years titled Funky Midnight Mover – The Studio Recordings (1962–1978). The compilation included all recordings originally issued during Pickett’s Atlantic years along with previously unreleased recordings. This collection was sold online only by Rhino.com.

Post-Atlantic recording career

Pickett continued to record with success on the R&B charts for RCA in 1973 and 1974, scoring four top 30 R&B hits with “Mr. Magic Man”, “Take a Closer Look at the Woman You’re With”, “International Playboy” (a re-recording of a song he had previously recorded for Atlantic on Wilson Pickett in Philadelphia), and “Soft Soul Boogie Woogie”. However, he was failing to cross over to the pop charts with regularity, as none of these songs reached higher than No. 90 on the Hot 100. In 1975, with Pickett’s once-prominent chart career on the wane, RCA dropped Pickett from the label. After being dropped, he formed the short-lived Wicked label, where he released one LP, Chocolate Mountain. In 1978, he made a disco album with Big Tree Records titled Funky Situation, which is a coincidence as, at that point, Big Tree was distributed by his former label, Atlantic. The following year, he released an album on EMI titled I Want You.

Pickett was a popular composer, writing songs that were recorded by many artists, including Van Halen, the Rolling Stones, Aerosmith, the Grateful Dead, Booker T. & the MGs, Genesis, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Hootie & the Blowfish, Echo & the Bunnymen, Roxy Music, Bruce Springsteen, Los Lobos, the Jam and Ani DiFranco, among others.

Pickett continued to record sporadically with several labels over the following decades (including Motown), occasionally making the lower to mid-range of the R&B charts, but he had no pop hit after 1974. His career was hindered by his addictions. His alcoholism was exacerbated by heavy cocaine use, and he became increasingly violent towards his family and bandmates.[18]

Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, despite his personal troubles, Pickett was repeatedly honored for his contributions to music. During this period, he was invited to perform at Atlantic Records’ 40th Anniversary concert in 1988, and his music was prominently featured in the 1991 film The Commitments, with Pickett as an off-screen character.

In the late 1990s, Pickett returned to the studio and received a Grammy Award nomination for the 1999 album It’s Harder Now. The comeback resulted in his being honored as Soul/Blues Male Artist of the Year by the Blues Foundation in Memphis.[19] It’s Harder Now was voted ‘Comeback Blues Album of the Year’ and ‘Soul/Blues Album of the Year.’

Pickett appeared in the 1998 film Blues Brothers 2000, in which he performed “634-5789” with Eddie Floyd and Jonny Lang. He was previously mentioned in the 1980 film Blues Brothers, which features several members of Pickett’s backing band, as well as a performance of “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love“.

He co-starred in the 2002 documentary Only the Strong Survive, directed by D. A. Pennebaker, a selection of both the 2002 Cannes and Sundance Film Festivals. In 2003, Pickett was a judge for the second annual Independent Music Awards to support independent artists’ careers.

Pickett spent the twilight of his career playing dozens of concert dates every year until the end of 2004, when he began suffering from health problems and took what was initially intended to be year-long break from performing.[1] While in the hospital, he returned to his spiritual roots and told his sister that he wanted to record a gospel album, but he never recovered.

On September 10, 2014, TVOne’s Unsung program aired a documentary that focused on Pickett’s life and career.[20] In 2023, Rolling Stone ranked Pickett at number 76 on its list of the 200 Greatest Singers of All Time.[21]

Personal life

Pickett was the father of four children. At the time of his death, he was engaged.[22]

Legal problems and drug abuse

Pickett’s struggle with alcoholism and cocaine addiction led to run-ins with the law.[18]

In 1991, Pickett was arrested for yelling threats while drunkenly driving his car over the front lawn of Donald Aronson, the mayor of Englewood, New Jersey.[23] He faced charges of drunk driving, refusing to take a breath test, and resisting arrest. Pickett agreed to perform a benefit concert in exchange for having the disorderly conduct and property damage charges dropped.[24] He performed his community service obligation.

In 1992, Pickett struck 86-year-old pedestrian Pepe Ruiz with his car in Englewood.[25] Police allegedly found six empty miniature vodka bottles and six empty beer cans in Pickett’s car.[26] Ruiz, who had helped organize the New York animation union, died later that year.[27] Pickett pleaded guilty to drunk driving charges.[28][24] He agreed to rehab and received a reduced sentence of one year in jail and five years probation.[29] A week after this incident, a judge ordered Pickett to move out of his home after his live-in girlfriend charged him with threatening to have her killed and throwing a vodka bottle at her.[26]

In 1996, Pickett was arrested for assaulting his girlfriend Elizabeth Trapp while under the influence of cocaine; she refused to press charges.[30] Pickett was charged with cocaine possession.[23]

Death

Pickett died on January 19, 2006, as a result of a heart attack.[31] He had been suffering from health problems for the last year of his life and had spent considerable time in the hospital. He died at a hospital in Reston, Virginia.[5][32] At the time of his death, Pickett was living in Ashburn, Virginia.[33] He was laid to rest in a mausoleum at Evergreen Cemetery in Louisville, Kentucky.[34] Pickett spent many years in Louisville. Pastor Steve Owens of Decatur, Georgia, presided over his funeral, and Little Richard, a long-time friend of Pickett’s, delivered the eulogy.[35][36]

Pickett was remembered on March 20, 2006, at New York’s B. B. King Blues Club with performances by the Commitments, Ben E. King, his long-term backing band the Midnight Movers, soul singer Bruce “Big Daddy” Wayne, and Southside Johnny in front of an audience that included members of his family, including two brothers.

Awards and nominations

Wilson was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1991.[37] In 1993, he was honored with a Pioneer Award by the Rhythm and Blues Foundation. In 2005, Wilson Pickett was voted into the Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Hall of Fame.[38] In 2015 Wilson Pickett was inducted into the National Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame.

Grammy Awards

He was nominated for five Grammy Awards during the course of his career.[11]

.mw-parser-output .awards-table td:last-child{text-align:center}| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1965 | “In the Midnight Hour” | Best R&B Performance | Nominated |

| 1967 | “Funky Broadway” | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Nominated |

| 1970 | “Engine #9” | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Nominated |

| 1987 | “In the Midnight Hour” (re-recording) | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Nominated |

| 1999 | It’s Harder Now | Best Traditional R&B Performance | Nominated |

Discography

Albums

| Year | Album | Chart positions | Label | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Pop [39] |

US R&B [39] | ||||

| 1963 | It’s Too Late | – | – | Double L Records DL-2300/SDL-8300 | |

| 1965 | In the Midnight Hour | 107 | 3 | Atlantic SD-8114 | |

| 1966 | The Exciting Wilson Pickett | 21 | 3 | Atlantic SD-8129 | |

| 1967 | The Wicked Pickett | 42 | 5 | Atlantic SD-8138 | |

| The Sound of Wilson Pickett | 54 | 7 | Atlantic SD-8145 | ||

| 1968 | I’m in Love | 70 | 9 | Atlantic SD-8175 | |

| The Midnight Mover | 91 | 10 | Atlantic SD-8183 | ||

| 1969 | Hey Jude | 97 | 15 | Atlantic SD-8215 | |

| 1970 | Right On | 197 | 36 | Atlantic SD-8250 | |

| Wilson Pickett in Philadelphia | 64 | 12 | Atlantic SD-8270 | ||

| 1971 | Don’t Knock My Love | 132 | 23 | Atlantic SD-8300 | |

| 1973 | Mr. Magic Man | 187 | 30 | RCA Victor LSP-4858 | |

| Miz Lena’s Boy | – | 34 | RCA Victor APL1-0312 | ||

| 1974 | Pickett in the Pocket | – | – | RCA Victor APL1-0495 | |

| 1975 | Join Me and Let’s Be Free | – | – | RCA Victor APL1-0856 | |

| 1976 | Chocolate Mountain | – | – | Wicked Records 9001 | |

| 1978 | Funky Situation | – | – | Big Tree/Atlantic BT-76011 | |

| 1979 | I Want You | – | 69 | EMI America SW-17019 | |

| 1981 | Right Track | – | – | EMI America SW-17043 | |

| 1987 | American Soul Man | – | 75 | Motown 6244-ML | |

| 1999 | It’s Harder Now | – | – | Bullseye Blues/Rounder BB-9625 | |

| “–” denotes releases that did not chart. | |||||

Live albums

- Live in Japan (1974, RCA Victor CLP2-0669 [2LP])

- Live and Burnin’ – Stockholm ’69 (2009, Soulsville Records SVR-25305 67390)

- Wilson Pickett Show: Live in Germany 1968 (2009, Crypt Records WP-1968)

Compilations

| Year | Album | Chart positions | Label | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Pop [39] |

US R&B [39] | ||||

| 1967 | The Best of Wilson Pickett | 35 | 9 | Atlantic SD-8151 | |

| 1971 | The Best of Wilson Pickett, Vol. II | 73 | 8 | Atlantic SD-8290 | |

| 1973 | Wilson Pickett’s Greatest Hits | 178 | 33 | Atlantic SD2-501 [2LP] | |

| 1992 | A Man and A Half: The Best of Wilson Pickett | – | – | Rhino R2-70287 | |

| 1993 | The Very Best of Wilson Pickett | – | – | Rhino R2-71212 | |

| 1998 | Take Your Pleasure Where You Find It: Best of the RCA Years | – | – | Camden 58814 | |

| 2006 | The Definitive Collection | – | – | Rhino R2-77614 | |

| 2010 | Funky Midnight Mover: The Atlantic Studio Recordings (1962–1978) | – | – | Rhino Handmade RHM2-07753[3] | |

| 2015 | Mr. Magic Man: The Complete RCA Studio Recordings | – | – | Real Gone Music RGM-0384 | |

| The Midnight Mover: Wilson Pickett & the Falcons (The Early Years 1957–1962) | – | – | Jasmine JASCD-936 | ||

| “–” denotes releases that did not chart. | |||||

Singles

| Year | Titles (A-side, B-side) Both sides from same album except where indicated |

Chart positions | Certifications | Album | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US [40] |

US R&B [41] |

UK [42] |

AUS [43] | ||||

| 1963 | “If You Need Me“ b/w “Baby, Call on Me” |

64 | 30 | – | – | It’s Too Late | |

| “It’s Too Late” b/w “I’m Gonna Love You” |

49 | 7 | – | – | |||

| “I’m Down to My Last Heartbreak” b/w “I Can’t Stop” |

95 | 27 | – | – | |||

| “My Heart Belongs to You” b/w “Let Me Be Your Boy” Reissue charted in 1965 |

109 | – | – | – | Non-album tracks | ||

| 1964 | “I’m Gonna Cry” b/w “For Better or Worse” |

124 | – | – | – | In the Midnight Hour | |

| “Come Home Baby” b/w “Take a Little Love” |

– | – | – | – | |||

| 1965 | “In the Midnight Hour“ b/w “I’m Not Tired” |

21 | 1 | 12 | – | ||

| “Don’t Fight It” b/w “It’s All Over” (from The Exciting Wilson Pickett) |

53 | 4 | 29 | – | |||

| 1966 | “634-5789 (Soulsville, U.S.A.)“ b/w “That’s a Man’s Way” (from In the Midnight Hour) |

13 | 1 | 36 | – | The Exciting Wilson Pickett | |

| “Ninety Nine and a Half (Won’t Do)” b/w “Danger Zone” |

53 | 13 | – | – | |||

| “Land of 1000 Dances“ b/w “You’re So Fine” |

6 | 1 | 22 | 22 |

| ||

| “Mustang Sally“ b/w “Three Time Loser” |

23 | 6 | 28 | 40 | The Wicked Pickett | ||

| 1967 | “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love“ b/w “Nothing You Can Do” |

29 | 19 | – | 57 | ||

| “I Found a Love – Part I” b/w “I Found a Love – Part II” |

32 | 6 | – | – | The Sound of Wilson Pickett | ||

| “You Can’t Stand Alone” | 70 | 26 | – | – | |||

| “Soul Dance Number Three” | 55 | 10 | – | – | |||

| “Funky Broadway“ b/w “I’m Sorry About That” |

8 | 1 | 43 | – | |||

| “I’m in Love” | 45 | 4 | – | – | I’m in Love | ||

| “Stagger Lee” | 22 | 13 | – | – | |||

| 1968 | “Jealous Love” | 50 | 18 | – | – | ||

| “I’ve Come a Long Way” | 101 | 46 | – | – | |||

| “She’s Lookin’ Good” b/w “We’ve Got to Have Love” |

15 | 7 | – | – | |||

| “I’m a Midnight Mover” b/w “Deborah” |

24 | 6 | 38 | – | The Midnight Mover | ||

| “I Found a True Love” b/w “For Better or Worse” |

42 | 11 | – | – | |||

| “A Man and a Half” b/w “People Make the World (What It Is)” |

42 | 20 | – | – | Hey Jude | ||

| “Hey Jude“ b/w “Search Your Heart” |

23 | 13 | 16 | 61 | |||

| 1969 | “Mini-skirt Minnie” b/w “Back in Your Arms” (from Hey Jude) |

50 | 19 | – | – | Non-album track | |

| “Born to Be Wild“ b/w “Toe Hold” |

64 | 41 | – | – | Hey Jude | ||

| “Hey Joe“ b/w “Night Owl” (from Hey Jude) |

59 | 29 | – | – | Right On | ||

| “You Keep Me Hangin’ On“ b/w “Now You See Me, Now You Don’t” (Non-album track) |

92 | 16 | – | – | |||

| 1970 | “Sugar, Sugar” | 25 | 4 | – | 77 | ||

| “Cole, Cooke, and Redding” | 91 | 11 | – | – | The Best of Wilson Pickett Vol. II | ||

| “She Said Yes” b/w “It’s Still Good” |

68 | 20 | – | – | Right On | ||

| “Engine No. 9” b/w “International Playboy” |

14 | 3 | – | – | In Philadelphia | ||

| 1971 | “Don’t Let the Green Grass Fool You” b/w “Ain’t No Doubt About It” |

17 | 2 | – | – | ||

| “Don’t Knock My Love – Pt. I“ b/w “Don’t Knock My Love – Pt. II” |

13 | 1 | – | – |

|

Don’t Knock My Love | |

| “Call My Name, I’ll Be There” b/w “Woman, Let Me Be Down Home” |

52 | 10 | – | – | |||

| “Fire and Water” b/w “Pledging My Love” |

24 | 2 | – | – | |||

| 1972 | “Funk Factory” b/w “One Step Away” |

58 | 11 | – | – | Non-album tracks | |

| “Mama Told Me Not to Come“ b/w “Covering the Same Old Ground” |

99 | 16 | – | – | Don’t Knock My Love | ||

| 1973 | “Mr. Magic Man” b/w “I Sho’ Love You” |

98 | 16 | – | – | Mr. Magic Man | |

| “Take a Closer Look at the Woman You’re With” b/w “Two Women and a Wife” |

90 | 17 | – | – | Miz Lena’s Boy | ||

| “International Playboy” b/w “Come Right Here” |

104 | 30 | – | – | In Philadelphia | ||

| 1974 | “Soft Soul Boogie Woogie” b/w “Take That Pollution Out Your Throat” |

103 | 20 | – | – | Miz Lena’s Boy | |

| “Take Your Pleasure Where You Find It” b/w “What Good Is a Lie” |

– | 68 | – | – | Pickett in the Pocket | ||

| “I Was Too Nice” b/w “Isn’t That So” |

– | – | – | – | |||

| 1975 | “The Best Part of a Man” b/w “How Will I Ever Know” |

– | 26 | – | – | Chocolate Mountain | |

| 1976 | “Love Will Keep Us Together” b/w “It’s Gonna Be Good” |

– | 69 | – | – | ||

| 1977 | “Love Dagger” b/w “Time to Let the Sun Shine on Me” (from A Funky Situation) |

– | – | – | – | Non-album track | |

| 1978 | “Who Turned You On” b/w “Dance You Down” |

– | 59 | – | – | A Funky Situation | |

| “Groovin'” b/w “Time to Let the Sun Shine on Me” |

– | 94 | – | – | |||

| 1979 | “I Want You” b/w “Love of My Life” |

– | 41 | – | – | I Want You | |

| 1980 | “Live with Me” b/w “Granny” |

– | 95 | – | – | ||

| 1981 | “Ain’t Gonna Give You No More” b/w “Don’t Underestimate the Power of Love” |

– | – | – | – | Right Track | |

| “Back on the Right Track” b/w “It’s You” |

– | – | – | – | |||

| 1982 | “Seconds” (with Jackie Moore) b/w “Seconds” (instrumental) |

– | – | – | – | Non-album tracks | |

| 1987 | “Don’t Turn Away” b/w “I Can’t Stop Now” |

– | 74 | – | – | American Soul Man | |

| “In the Midnight Hour” (re-recording) b/w “Just Let Her Know” |

– | – | 62 | – | |||

| 1988 | “Love Never Let Me Down” b/w “Just Let Her Know” |

– | – | – | – | ||

| “–” denotes releases that did not chart or were not released in that territory. | |||||||

References

- ^ a b .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit;word-wrap:break-word}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:”\”””\”””‘””‘”}.mw-parser-output .citation:target{background-color:rgba(0,127,255,0.133)}.mw-parser-output .id-lock-free.id-lock-free a{background:url(“//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/65/Lock-green.svg”)right 0.1em center/9px no-repeat}.mw-parser-output .id-lock-limited.id-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .id-lock-registration.id-lock-registration a{background:url(“//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg”)right 0.1em center/9px no-repeat}.mw-parser-output .id-lock-subscription.id-lock-subscription a{background:url(“//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg”)right 0.1em center/9px no-repeat}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url(“//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg”)right 0.1em center/12px no-repeat}body:not(.skin-timeless):not(.skin-minerva) .mw-parser-output .id-lock-free a,body:not(.skin-timeless):not(.skin-minerva) .mw-parser-output .id-lock-limited a,body:not(.skin-timeless):not(.skin-minerva) .mw-parser-output .id-lock-registration a,body:not(.skin-timeless):not(.skin-minerva) .mw-parser-output .id-lock-subscription a,body:not(.skin-timeless):not(.skin-minerva) .mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background-size:contain;padding:0 1em 0 0}.mw-parser-output .cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:none;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;color:var(–color-error,#d33)}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{color:var(–color-error,#d33)}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#085;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right{padding-right:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .citation .mw-selflink{font-weight:inherit}@media screen{.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{color:#18911f}}@media screen and (prefers-color-scheme:dark){html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{color:#18911f}}Leeds, Jeff (January 20, 2006). “Obituary: Wilson Pickett, 64, singer of ‘the Midnight Hour’“. The New York Times.

- ^ “EMI America Records Discography” (PDF). Bsnpubs.com. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Strong, Martin C. (2000). The Great Rock Discography (5th ed.). Edinburgh: Mojo Books. pp. 745–746. ISBN 1-84195-017-3.

- ^ a b c “Wilson Pickett”. Rockhall.com. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- ^ a b Boucher, Geoff (January 20, 2006). “Wilson Pickett, 64; Soul Legend Sang Hits ‘In the Midnight Hour,’ ‘Mustang Sally’“. Los Angeles Times.

- ^ “Bio”. Official Website. Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- ^ Guralnick 1999, pp. 95–96.

- ^ The Bert Berns Story, Mr. Success, Vol. 2, Ace Records, London, England, 2010, liner notes

- ^ Gilliland, John (1969). “Show 51 – The Soul Reformation: Phase three, soul music at the summit. [Part 7] : UNT Digital Library” (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- ^ a b c d e Murrells, Joseph (1978). The Book of Golden Discs (2nd ed.). London: Barrie nd enkins Ltd. pp. 194, 210, 227 & 301. ISBN 0-214-20512-6.

- ^ a b “Wilson Pickett”. Recording Academy Grammy Awards.

- ^ Pickett, Wilson, The Very Best of Wilson Pickett, Atlantic Recording Corp. and Rhino records Inc., 1993, liner notes by Kevin Phinney.

- ^ In the Midnight Hour/634-5789 Retrieved May 31, 2022

- ^ Guralnick 1999, p. 259.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). “Consumer Guide ’70s: P”. Christgau’s Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 089919026X. Retrieved March 10, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (August 19, 1971). “Rousing ‘Soul to Soul’“. The New York Times.

- ^ “Best Selling Soul LP’s” (PDF). Billboard. October 30, 1971. p. 33.

- ^ a b De Stefano, George (February 8, 2017). “Pickett Was Wicked Good and Wicked Bad: ‘In the Midnight Hour’“. PopMatters.

- ^ “Blues.org”. Blues.org. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- ^ “Wilson Pickett Obituary on Legacy.com”. Legacy.com. January 19, 2006. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ “The 200 Greatest Singers of All Time”. Rolling Stone. January 1, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ Schudel, Matt (January 19, 2006). “‘Midnight Hour,’ ‘Mustang Sally’ R& B Singer Wilson Pickett”. Washington Post.

- ^ a b Leigh, Spencer (January 21, 2006). “Wilson Pickett”. The Independent.

- ^ a b “Pickett Will Perform Benefit To Have Disorderly Conduct, Other Raps Dismissed”. Jet. Johnson Publishing Company. July 26, 1993.

- ^ “Pickett to Perform in Concert to Settle Dispute with Mayor”. Jet. March 15, 1993. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ a b “Pickett Gets Summons For Alcohol Bottles In Car After Accident”. Jet: 60. May 11, 1992.

- ^ “Cartoon Diary: August 1, 1944”. Filboidsudge.blogspot.com. August 1, 2005. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- ^ “Pickett Pleads Guilty To Drunken Driving Charges”. Jet: 14. July 19, 1993.

- ^ Leeds, Jeff (January 20, 2006). “Wilson Pickett, 64, Soul Singer of Great Passion, Dies”. The New York Times.

- ^ “New Jersey Police Look Into Charges Famed Singer Wilson Pickett Beat His Girlfriend”. Jet. 89 (24): 53. April 29, 1996.

- ^ “Wilson Pickett Dies Of Heart Attack – CBS News”. www.cbsnews.com. January 19, 2006. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ Rock, Doc. “The Dead Rock Stars Club 2006 January To June”. Thedeadrockstarsclub.com. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ Brulliard, Karin (January 28, 2006). “A Soulman’s Suburban Twilight”. Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Fletcher, Tony (July 25, 2017). In the Midnight Hour: The Life & Soul of Wilson Pickett. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190252946 – via Google Books.

- ^ “Wilson Pickett | Bio, Pictures, Videos”. Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 16, 2013. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ “Mourners remember music of soul singer Wilson Pickett”. The Gadsden Times. January 28, 2006.

- ^ “Wilson Pickett”. Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

- ^ “Michigan Rock and Roll Legends – WILSON PICKETT”. Michiganrockandrolllegends.com. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c d “Wilson Pickett – Awards”. AllMusic. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ Joel Whitburn. Top Pop Singles (12th ed.). pp. 759–760.

- ^ “Wilson Pickett Songs ••• Top Songs / Chart Singles Discography ••• Music VF, US & UK hits charts”. www.musicvf.com. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 426. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- ^ “Australian Chart Books”. www.australianchartbooks.com.au. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ a b “British certifications – Wilson Pickett”. British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved October 14, 2023. Type Wilson Pickett in the “Search BPI Awards” field and then press Enter.

- ^ a b “American certifications – Wilson Pickett”. Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

Bibliography

- Ross, Andrew and Rose, Tricia (Ed.). (1994). Microphone Fiends: Youth Music and Youth Culture. Routledge: New York. ISBN 0-415-90908-2

- Hirshey, Gerri. Nowhere to Run: The Story of Soul Music. Da Capo Press; Reprint edition (September 1, 1994), ISBN 0-306-80581-2

- Hirshey, Gerri (February 9, 2006). Wilson Pickett, 1941–2006. Rolling Stone No. 933.

- Sacks, Leo. Liner notes to A Man and a Half: The Best of Wilson Pickett (1992, Rhino).

- Guralnick, Peter (1999). Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm and Blues and the Southern Dream of Freedom. Back Bay Books. ISBN 978-0-316-33273-6. OCLC 41950519.

External links

- Wilson Pickett discography at Discogs

- Wilson Pickett at IMDb

- Unterberger, Richie. Wilson Picket 1999 induction profile via Alabama Music Hall of Fame

- Wilson Pickett via classicbands.com

- Escott, Colin. “The Wicked Wilson Pickett”.

- Boone, Mike. “In The Midnight Hour”, via soul-patrol.com

- Associated Press (January 19, 2006). “Soul Singer Wilson Pickett Dies at 64”

- Muskal, Michael (January 19, 2006). “Soul Pioneer Wilson Pickett Dies at 64”. Los Angeles Times

- Epstein, Dan (January 19, 2006). Soul Legend Wilson Pickett Dies”. Rolling Stone

- Jansen, Lex (January 19, 2006). Wilson Pickett at the Heart of Rock and Soul

- Dr. Frank Hoffmann, Article About Wilson Pickett

- Wilson Pickett at Rolling Stone

- Wilson Pickett article Archived January 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopedia of Alabama

| .mw-parser-output .navbar{display:inline;font-size:88%;font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .navbar-collapse{float:left;text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .navbar-boxtext{word-spacing:0}.mw-parser-output .navbar ul{display:inline-block;white-space:nowrap;line-height:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::before{margin-right:-0.125em;content:”[ “}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::after{margin-left:-0.125em;content:” ]”}.mw-parser-output .navbar li{word-spacing:-0.125em}.mw-parser-output .navbar a>span,.mw-parser-output .navbar a>abbr{text-decoration:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-mini abbr{font-variant:small-caps;border-bottom:none;text-decoration:none;cursor:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-full{font-size:114%;margin:0 7em}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-mini{font-size:114%;margin:0 4em}html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .navbar li a abbr{color:var(–color-base)!important}@media(prefers-color-scheme:dark){html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .navbar li a abbr{color:var(–color-base)!important}}@media print{.mw-parser-output .navbar{display:none!important}} | |

|---|---|

| Albums |

|

| Singles |

|

| Related articles | |

| Performers | |

|---|---|

| Early influences | |

| Non-performers (Ahmet Ertegun Award) | |

| Lifetime achievement | |